So now that you know how to make gradients, it is time to put them to use. The best way I can demonstrate how to do this is to show you how to copy a photographic reference. Now, I had originally intended to start with something smooth and simple — a single subject, like a vase — that would demonstrate large regions of value that are relatively simple to recreate. Two things precluded me from doing this, however: I could not find a subject that matched that description outside of my apartment, and the inside of my apartment is notoriously dark. I thus enacted plan B: take a photo of something that had a gradient and use that. As such, the image I would like you to draw is this:

Now, you are probably thinking something along the lines of, “you want me to draw that!? I just learned how to make gradients about a week ago!”

|

| He's certainly thinking it. |

Yes. And I really think you can. Of course, this "lesson" will follow my specific process for achieving this, and it may not entirely work for you. I hope that if nothing else, you will be able to discover your own method by trying to draw this picture.

But first, two things. This picture is complicated, and it is a little too large to reproduce in its entirety just for the purpose of practice. We will focus on this region here to make this a little more reasonable:

Since I am not covering the subject of color this early on (I lack a reasonable amount of experience with it, myself), I will “gray-scale” the image so that we only have to focus on its values.

|

| Open this image in another tab so you can look at it without any distractions, or download it to your computer and use some kind of image-viewer. I don't really care what you do with it, nor do I care about you trying to copy it (obviously). |

This last image will be the “reference” for your drawing. Believe it or not, it does have two characteristics that I think make it good for practice. First, it contains a few regions with really clear gradients. Second, it lacks a bit of familiarity due to it being cropped — this helps with ignoring the “shapes” of objects, and instead leads you to focus only on their values.

A few final notes before we begin. First, this image took me roughly three-and-a-half hours to reproduce. That might not be very relevant as you may be faster or slower than me, but I figured it would be worthy to mention in the event that you want a rough estimate for how long this can take to do. Second, I used only one 0.7mm HB-lead mechanical pencil to do this. This is the regular kind that you can buy in cheap packs at most retail stores. It is my favorite drawing tool, the one with which I have the most experience, and also one that you probably have lying around somewhere.

|

| This, right here. I think its technical name is the "BiC Sparkle, of the orange variety." Definitely high-end art school stuff. |

If you don’t, any regular, wooden pencil will probably work for this. I don’t recommend working with ballpoint or cross-hatching with an ink-pen, because they don’t function in a similar enough way.

Third, you will need to be able to “bend” your gradients, or make them fit various shapes. I didn’t figure that this needed any additional explanation in the last post because it really is just the same thing, but instead of using a rectangle, you are using curves. Further, you will need to be able to control how quickly your gradient “falls off,” or the distance between dark and light values. Also, you will need to be able to recognize the sharp boundaries between large regions of flat value — or, worded less pompously, just be able to fill in a space with one value and a different space with another. Finally, when shading, hold your pencil further back in your hand than you would while writing, so you can make broad, sweeping marks. Remember to draw lightly.

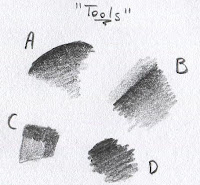

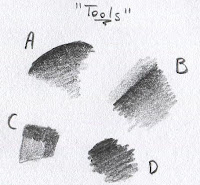

|

A: "Bending your gradient."

B: "Falloff. The top has a sharp falloff, and the bottom has a dull falloff."

C: "Regions of value. I won't believe you if you say you can't do this."

D: "A blob-like shape that will come in handy when I try to describe the way I make some of the texture much later on." |

|

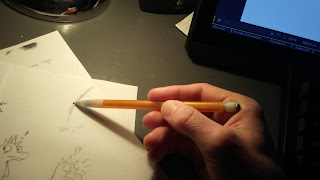

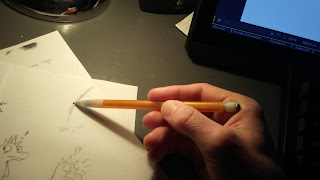

| And this is how you should hold your pencil when shading. |

It looks wobbly and imprecise. It is, and that is kind of the point. It takes advantage of how your wrist bends to quickly lay down long sweeps of the same value.

Setting up your scene with guiding lines.

Alright, now we can start. The first part of my process is to lay down some guiding lines.

This is one of the most important things we can do to start a successful image; no amount of skillful shading or detail will save a drawing made on a poor base. That is what this step establishes: a base for the rest of your drawing. This stage gives you an idea of what the final image will look like.

The way we can create a good base for this image is to start from the biggest, simplest shapes and move inward. Remember to keep an eye on your reference for the majority of the time you are trying to draw it; a lot of the skill of drawing lies in how well you observe your subject. Now, you are probably wondering what the difference is between these and outlines.

|

| Yeah, I figured. |

Well, outlines try to divide scenes into individual elements. You would use them, for instance, to separate a character from a background, or parts of a character from other parts of that same character (like, the eyes from the head). They also tend to be very bold, and stand out as a part of the final image. The problem with looking at these as outlines, particularly as a beginner, is that they invite you to draw a shape by the way you think it looks, rather than by the way you are seeing it. In this image, we are not drawing a banister, apartment building, and numerous complicated systems of railings. Instead, we are drawing shapes that will eventually be an illusion of these things. This is an important point; drawing is all about approximation. The closer your approximation is to an image of these things, the better of an artist you are (in an extremely rough nutshell). We should lay down these lines by looking at divisions in contrast, rather than the implied shape of the object. A good example of this is the line near the center of the image — the one that intersects that broken-out knot of wood. That region of our source image is black. Rather than trying to just outline that blob, I created a line here that would serve as the blackest part of my gradient. We can start our gradient along that line, and bend it into the knot to create a more realistic shading.

This part might give you an idea of what outlines really are: the divisions between regions of value in a way that symbolically represents an object. A lot can be written on this topic, and I plan to later.

You can use a ruler to make these lines, though I find “tracing” the red line on a lined piece of paper to end up looking more natural. The important thing is that you draw as lightly as possible! You will want to correct any major flaws in the composition of your drawing during this stage, so you won’t have to later. Spend a good amount of time on this stage, look at where these regions intersect the edges of the image; I started with the banister in front by looking at where it touched the edges of the encompassing square. Notice that these lines are pretty loose and “sketchy.” That’s something I encourage, because they allow you to play around a bit with the shape later.

A final note: I just used lines to represent the metal pipes that make up the railing on the other deck.

I spent about forty-one minutes on this stage to get it to my liking, though it might not look like it.

Starting the Gradients…

Okay, so we finished our lines and now we’ve moved onto starting on those gradients. Here is really where those lines really start to show their usefulness. I usually start with the darkest parts of the image. We won’t work these areas into a jet-black just yet — we can do that as we continue to draw. The biggest reason that we are using this image is actually apparent in this step: the black-painted metal of the pipe on the banister is a dark region with a very apparent couple of gradients. Once that pipe hits black, we can just shade all the way down to the bottom of that old guideline with a dark black.

With the pre-established guidelines, we can be sure that where we are starting these blacks is pretty much correct, and we will not have to erase them later. If you lay them on lightly, gently building up layers, you should be able to “nibble” into them with the eraser, though. The supporting piece of wood near the bottom right of the image is a good example of what we are trying to accomplish during this step: darks and a little bit of midtones to start off our work on shading this entire image.

Alright, it’s not very impressive yet, but we are getting somewhere. What is important is that we are working very roughly, and loosely; look at the downward staircase in the middle-left of the image. Those lines do not look like they were put there with careful planning, just controlled scribbling. This is what we want. We can come back later and straighten these out once the gradients and values are in place.

Wow, this post has started to get a little long. I hadn't initially planned on splitting it up, but this is turning into a bit of a beast. If you're still with me, great! Hopefully you will have a picture that you are proud of by the end. If not, well, keep practicing and I guarantee that you will draw better. In any case, I will post the next two parts very soon.